Definition

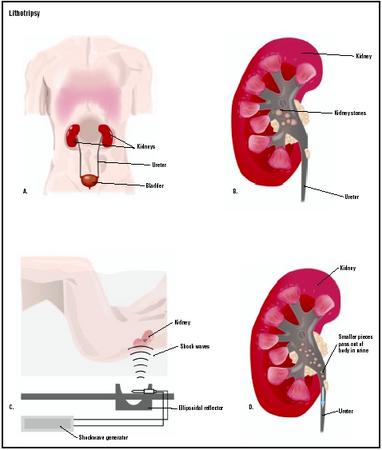

Lithotripsy is the use of high-energy shock waves to fragment and disintegrate kidney stones. The shock wave, created by using a high-voltage spark or an electromagnetic impulse outside of the body, is focused on the stone. The shock wave shatters the stone, allowing the fragments to pass through the urinary system. Since the shock wave is generated outside the body, the procedure is termed extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL). The name is derived from the roots of two Greek words, litho , meaning stone, and trip , meaning to break.

Purpose

ESWL is used when a kidney stone is too large to pass on its own, or when a stone becomes stuck in a ureter (a tube that carries urine from the kidney to the bladder) and will not pass. Kidney stones are extremely painful and can cause serious medical complications if not removed.

Demographics

For an unknown reason, the number of persons in the United States developing kidney stones has been increasing over the past 20 years. White people are more prone to develop kidney stones than are persons of color. Although stones occur more frequently in men, the number of women who develop them has been increasing over the past 10 years, causing the ratio to change. Kidney stones strike most people between the ages of 20 and 40. Once persons develop more than one stone, they are more likely to develop others. Lithotripsy is not required for treatment in all cases of kidney stones.

Description

Lithotripsy uses the technique of focused shock waves to fragment a stone in the kidney or the ureter. The affected person is placed in a tub of water or in contact with a water-filled cushion. A sophisticated machine called Lithotripter produces the focused shock waves. A high-voltage electrical discharge is passed through a spark gap under water. The shock waves thus produced are focused on the stone inside the person’s body. The shock waves are created and focused on the stone with the help of a machine called C-Arm Image Intensifier. The wave shatters and fragments the stone. The resulting debris, called gravel, can then pass through the remainder of the ureter, through the bladder, and through the urethra during urination. There is minimal chance of damage to skin or internal organs because biologic tissues are resilient, not brittle, and because the shock waves are not focused on them.

)

kidney and strikes the stone. At the edge of the stone, energy is transferred into the stone, causing small cracks to form on the edge of the stone. The same effect occurs when the shock wave exits the stone. With successive shock waves, the cracks open up. As more cracks form, the size of the stone is reduced. Eventually, the stone is reduced to small particles, which are then flushed out of the kidneys or ureter naturally during urination.

Diagnosis/Preparation

ESWL should not be considered for persons with severe skeletal deformities, people weighing more than 300 lb (136 kg), individuals with abdominal aortic aneurysms, or persons with uncontrollable bleeding disorders. Women who are pregnant should not be treated with ESWL. Individuals with cardiac pacemakers should be evaluated by a cardiologist familiar with ESWL. The cardiologist should be present during the ESWL procedure in the event the pacemaker needs to be overridden.

Prior to the lithotripsy procedure, a complete physical examination is performed, followed by tests to determine the number, location, and size of the stone or stones. A test called an intravenous pyelogram (IVP) is used to locate the stones, which involves injecting a dye into a vein in the arm. This dye, which shows up on x ray, travels through the bloodstream and is excreted by the kidneys. The dye then flows down the ureters and into the bladder. The dye surrounds the stones. In this manner, x rays are used to evaluate the stones and the anatomy of the urinary system. Blood tests are performed to determine if any potential bleeding problems exist. For women of childbearing age, a pregnancy test is done to make sure they are not pregnant. Older persons have an EKG test to make sure that no potential heart problems exist. Some individuals may have a stent placed prior to the lithotripsy procedure. A stent is a plastic tube placed in the ureter that allows the passage of gravel and urine after the ESWL procedure is completed.

The process of lithotripsy generally takes about one hour. During that time, up to 8,000 individual shock waves are administered. Depending on a person’s pain tolerance, there may be some discomfort during the treatment. Analgesicsmay be administered to relieve this pain.

Aftercare

Most persons pass blood in their urine after the ESWL procedure. This is normal and should clear after several days to a week. Lots of fluids should be taken to encourage the flushing of any gravel remaining in the urinary system. Treated persons should follow up with a urologist in about two weeks to make sure that everything is progressing as planned. If a stent has been inserted, it is normally removed at this time.

Risks

Abdominal pain is fairly common after ESWL, but it is usually not a cause for worry. However, persistent or severe abdominal pain may imply an unexpected internal injury. Occasionally, stones may not be completely fragmented during the first ESWL treatment and further lithotripsy procedures may be required.

Some people are allergic to the dye material used during an IVP, so it cannot be used. For these people, focused sound waves, called ultrasound, can be used to identify where the stones are located.

Normal results

In most cases, stones are reduced to gravel and passed within a few days. Individuals may return to work whenever they feel able.

Morbidity and mortality rates

Colicky renal pain is very common when gravel is being passed. Other problems may include perirenal hematomas (blood clots near the kidneys) in 66% of the cases; nerve palsies; pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas); and obstruction by stone fragments. Death is extremely rare and usually due to an undiagnosed associated or underlying condition that is aggravated by the lithotripsy procedure.

Alternatives

Before the advent of lithotripsy, surgery was used to remove kidney stones. This approach is uncommon today, but occasionally used when other conditions prevent the use of lithotripsy. Attempts are occasionally made to change the pH of urine so as to dissolve kidney stones. This treatment has limited success.

Resources

books

Field, Michael, David Harris, and Carol Pollock. The Renal System. London: Churchill Livingstone, 2001.

Parker, James N. The 2002 Official Patient’s Source Book on Kidney Stones. Logan, UT: ICON Health, 2002.

Tanagho, Emil A., and Jack W. McAninch. Smith’s General Urology, 15th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000.

Walsh, Patrick C., and Alan B. Retik. Campbell’s Urology, 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2002.

periodicals

Ather, M. H., and M. A. Noor. “Does Size and Site Matter for Renal Stones Up to 30 mm in Size in Children Treated by Extracorporeal Lithotripsy?” Urology 61, no.1 (2003): 212–215.

Downey, P., and D. Tolley. “Contemporary Management of Renal Calculus Disease.” Journal of the Royal College of Surgery (Edinburgh) 47, no.5 (2002): 668–675.

Hochreiter, W. W., H. Danuser, M. Perrig, and U. E. Studer. “Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy for Distal Ureteral Calculi.” Journal of Urology 169, no.3 (2003): 878–880.

Rajkumar, P., and G. F. Schmitgen. “Shock Waves Do More Than Just Crush Stones: Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy in Plantar Fasciitis.” International Journal of Clinical Practice 56, no.10 (2002): 735–737.

organizations

American Foundation for Urologic Disease. 1128 North Charles Street, Baltimore, MD 21201. (800) 242-2383 or (410) 468-1800. http://admin@afud.org. http://www.afud.org .

American Lithotripsy Society. 305 Second Avenue, Suite 200, Waltham, MA 02451.

American Medical Association. 515 N. State Street, Chicago, IL 60610. (312) 464-5000. http://www.ama-assn.org .

American Urological Association. 1120 North Charles Street, Baltimore, MD 21201-5559. (410) 727-1100. http://www.auanet.org/index_hi.cfm .

National Kidney Foundation. 30 East 33rd Street, New York, NY 10016. (800) 622-9010. (781) 895-9098. Fax: (781) 895-9088. E-mail: http://als@lithotripsy.org. http://www.kidney.org .

other

Case Western Reserve University. [cited March 17, 2003] http://www.cwru.edu/artsci/dittrick/artifactspages/b-2lithotripsy.htm .

Global Lithotripsy Services. [cited March 17, 2003] http://www.gls-lithotripsy.com/Howdoes.html .

Lifespan. [cited March 17, 2003] http://www.lifespan.org/mininvasive/revised/patient/gallstones/lithotripsy.htm .

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. [cited March 17, 2003] http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health/urolog/pubs/stonadul/stonadul.htm#whogets .

National Library of Medicine. [cited March 17, 2003] http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/007113.htm .

L. Fleming Fallon, Jr, MD, DrPH

WHO PERFORMS THE PROCEDURE AND WHERE IS IT PERFORMED?

Lithotripsy is performed by a technician or other individual with specialized training under the supervision of a physician. The physician in charge usually has specialized training in urology. Lithotripsy is most often performed as an outpatient procedure in a facility affiliated with a hospital.

Source Read more: http://www.surgeryencyclopedia.com/La-Pa/Lithotripsy.html#ixzz53XzP0D6h